From the chance to learn Biblical Hebrew and New Testament Greek, to gaining a deeper understanding of the Trinity, to exploring the contribution of the early church to Christian doctrine, here is a full list of all the subjects on offer at Ming Hua for the Bachelor of Theology and Master of Theology programmes in the new semester, starting on 4 September, 2023.

Bachelor of Theology

Biblical Studies:

Introduction to Biblical Languages (THL100)

For students who aspire to read the Bible in the languages in which it was written, this subject offers an introduction to Biblical Hebrew and New Testament Greek. Students will learn the alphabets of both languages, as well as their basic grammatical features and elementary vocabulary. They will also look at some of the cultural dimensions of the biblical texts that are preserved in the ancient languages, and consider the impact these have on how the texts should be interpreted.

Lecturer: Revd Dr Jim West

Day & Time: Wednesdays, 7pm – 9:15pm through Zoom

Introduction to New Testament Studies (THL106)

This interesting subject provides an overview of the various writings that make up the New Testament, ranging from the four Gospels to the apocalyptic literature. Students will look at the historical context of the books of the New Testament, as well as their literary and theological features. They will also be introduced to the basic critical skills used in New Testament interpretation, including exegetical skills, and consider the history of New Testament studies and the different critical approaches to New Testament texts.

Lecturer: LIM Chin Ming Stephen

Day & Time: Thursdays, 7pm to 9.15pm

The Synoptic Gospels (THL208)

The three Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, all tell the story of Jesus’ life but in their own distinct ways. While they include many of the same stories, and at times use identical wording, they also contain notable differences. Students taking this subject will explore these differences in depth, looking at the historical, literary, cultural and religious contexts in which they were written. They will also assess these Gospels as a source for understanding Jesus and explore the puzzle of how they relate to each other.

Lecturer: Revd Dr Eric Lau

Day & Time: Wednesdays, 7pm to 9.15pm

Systematic Theology

Being the Church (THL113)

The Church has a central place in Christian faith as the people of God are called out for life, ministry and mission. This subject explores the theological and scriptural basis for ‘being the Church’ and its implications for Christian living in the contemporary world. Topics explored include the traditional ‘marks’ of the Church, its unity and diversity in the ecumenical context, and contemporary critiques of church life and practice. A central focus throughout will be the perennial challenge for Christians in all times and all places to ‘be the church’ and what that means in a complex and ever-changing world.

Lecturer: Dr Matthew Jones

Day & Time: Mondays, 7pm to 9.15pm

The Triune God (THL316)

The Trinity is one of the most complex, yet central, doctrines of the Christian faith. This subject explores the development of the Christian understanding of God as ‘three persons in one God’, looking at the biblical origins of the doctrine, as well as key historical and theological developments in the first five centuries following Jesus’ death and resurrection. It will also explore how the doctrine has been rejuvenated in recent decades and the implications this revival has for theology, ecclesiology, worship and interfaith dialogue.

Lecturer: Dr Matthew Jones

Day & Time: Thursdays, 7pm to 9.15pm

Church History:

Early Church History (THL131)

Some of the most important doctrines of Christianity emerged out of the Early Church. This exciting subject looks at the contributions made by the Apostolic Fathers and Early Christian Apologists, as well as exploring church-state relations and the theology that emerged from the Councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon. It also examines early Christian monasticism, issues of ethnicity and gender, mission and the claims of the Bishop of Rome to supremacy, while introducing students to the skills needed to study church history.

Lecturer: Mr William Lee

Day & Time: Tuesdays, 7pm to 9.15pm

Religion in Chinese Culture (THL257)

Students studying this subject will be given a fascinating insight into religious life in Greater China, as well as the Chinese diaspora in Asia and beyond, looking at the interaction of religion with society and culture in both historical and contemporary situations. The subject focuses on Daoism, Buddhism, Chinese folk religion and Confucianism, giving students an insight into the key issues in interpreting the relationship between traditional Chinese religion and Christianity, as well as looking at Islam and various minority traditions in China.

Lecturer: Dr Rowena Chen

Day & Time: Mondays, 7pm to 9.15pm

Practical Theology:

Christian Worship (THL115)

This subject explores the history and practice of worship across a variety of Christian traditions, including contemporary and blended worship. There will be a particular focus on the effects of rites, symbols, words and music in worship, as well as looking at liturgical forms, architecture and mission in this context. Students will also explore the importance of worship in the formation of Christian identity, including the relationship of worship to pastoral care.

Lecturer: Revd Dr Chun-wai Lam

Day & Time: Wednesdays, 7pm to 9.15pm

Master of Theology

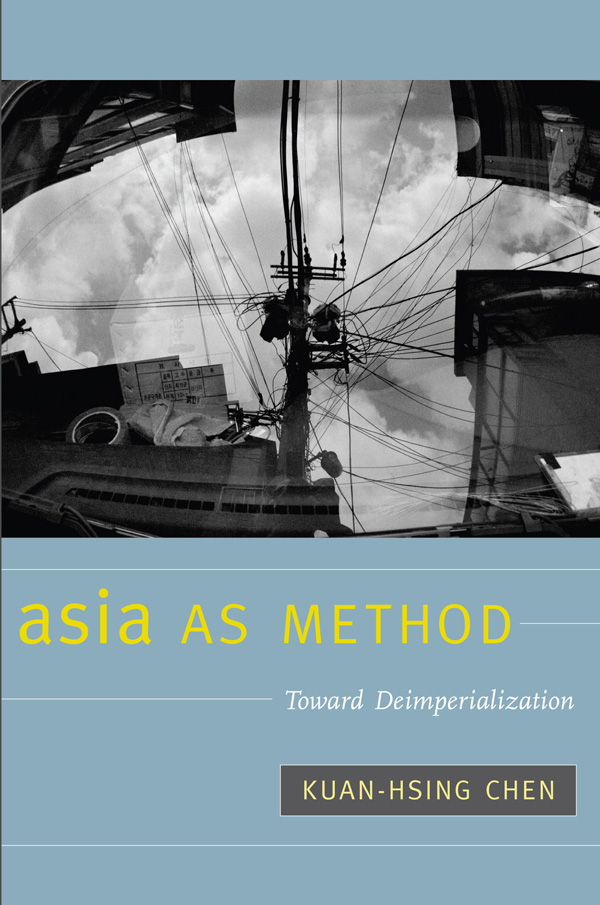

The Philosophy of Religious History (THL533)

This fascinating subject addresses the development of historical thinking and method in the flow of time and space, especially in modern and post-modern thinking, with reference to both religious history and the discipline of history generally. Students will consider the meaning, purpose and social functions of historical writing about religion, as well as assess critically the methods, models and interpretations employed by different historical traditions and religions. In addition, they will examine trends in recent historical thought and practice, and explore the influence of disciplines such as theology, sociology and anthropology on religious history, as well as of movements such as Marxism, postmodernism, feminism and post-colonialism.

Lecturer: Revd Prof Philip Wickeri

Day & Time: Thursdays, 2pm to 4.15pm

Contemporary Theology in a Global Context (THL512)

All theology is contextual in that it reflects the locations, situations and questions that surround the theologian. This subject is an exciting journey through some of these fascinating twists and turns, which will include exploring the relationship between theology and culture, the emergence of eco-theology in response to the environmental crisis, the contribution of feminist theology, and the emergence of distinct Asian theologies that see God in diverse and yet interconnecting ways. Students will explore their own encounter with God in their own contexts and the challenges, questions, and potentialities it raises.

Lecturer: Dr Matthew Jones

Day & Time: Tuesdays, 7pm to 9.15pm

For enquiries,

Email admission@minghua.edu.hk

Whatsapp 9530 7241

Click here to enrol.