LIM Chin Ming, Stephen reflects on Chen Kuan-Hsing’s Asia as: Towards Deimperialisation and reading the Bible in Asia.

The movement of ‘doing theologies in Asian ways with Asian resources’ can be traced back to at least the 1980s. It was a key project of the Programme for Theology and Cultures in Asia (PTCA) to think about what it means to do theology, and more generally, read the Bible in Asia with Asian epistemologies.[1] In recent years, we have also witnessed a gathering interest in reviving this area of study. That being said, my personal lament is that much of these efforts have not percolated into theological education, where Asian contexts are ultimately still seen as places and objects to apply western derived theologies, biblical hermeneutics, methods, and theories.

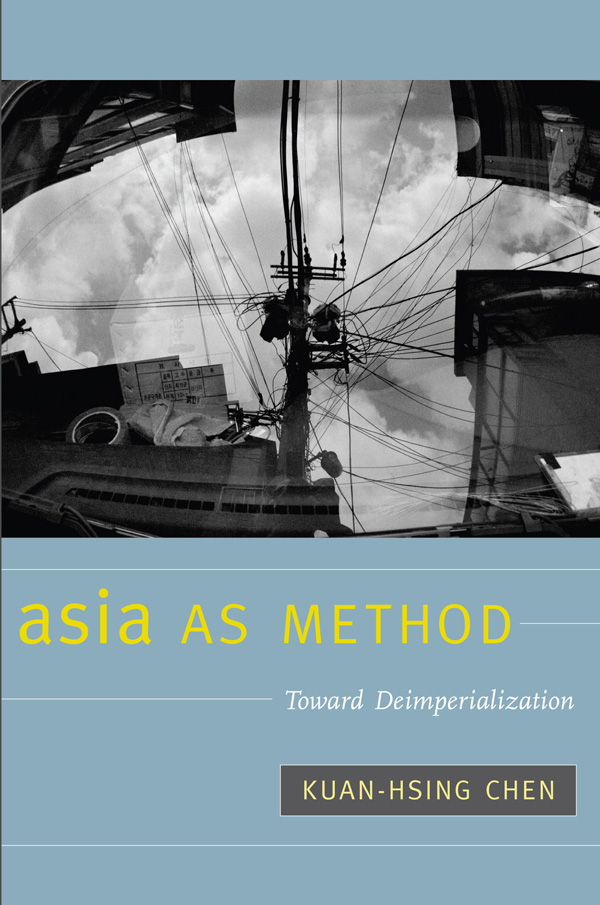

It is within this conundrum that Chen Kuan-Hsing’s Asia as Method: Towards Deimperialisation (Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2010) becomes a relevant dialogical partner, despite being written explicitly for Asian contexts in general, rather than specifically for Christians or the church. Published in both Chinese and English, his main concern is how we can move beyond the trappings of our ex-colonial masters who continue to dominate the fields of knowledge production around the world. My intention is not to review this book in the traditional sense as it has been reviewed many times elsewhere. Rather, within this limited space, I wish to highlight key intersecting points between his work and reading the Bible in Asia.

The main contribution that Chen offers, in my view, is why efforts at recovering Asian systems of knowledge production have stalled in many areas, in which I include Christianity and the church. He argues that efforts of decolonisation in the post-World War period were disrupted by the Cold War, and it is only in the age of neoliberal globalization that we see it unfolding again. He is not limiting decolonisation to just the time of anti-colonial struggle, but more importantly describing it as an endeavour to ‘reflectively work out a historical relation with the former colonizer, culturally, politically, and economically’ through the painful practice of ‘self-critique, self-negation, and self-rediscovery’ because our desire is to ‘form a less coerced and more reflexive and dignified subjectivity’ (p. 3). Concomitantly, he argues that decolonisation cannot do without deimperialisation, which is primarily the work of the ‘colonising or imperialising population’, both in the West and in the rest of the world, to ‘examine the conduct, motives, desires, and consequences of the imperialist history that has formed its own subjectivity’ (p. 4). It is within these twin processes of decolonisation and deimperialisation that he locates his proposition of ‘Asia as Method’.

In the interest of space, I can only address two points of intervention. In the light of the above, we need to restart and/or continue efforts of decolonization. In his chapter on ‘Decolonization: A Geocolonial Historical Materialism’, Chen surveys the strengths and weaknesses of the different responses to the colonising experience – nationalism, nativism, and civilisationism. In short, what is important for me as an Asian (Christian) subject is to embrace the journey of self-determination and self-(re)discovery, while being wary that I myself am not exempt from the problems of ethnic chauvinism and exclusionism. When applied to the task of reading the Bible, we need to think about how we read the Bible as Asians with Asian ideas, Asian songs, Asian stories, Asian philosophies and so on, both from the past and in the present. At the same time, we must also allow the Bible to critique our (Asian) ways of thinking and life.

The second point is the question of the West. This is especially pertinent for the church and even more so for the Bible, since the Bible has come to many parts of Asia on the sails of our ex-colonial masters. Chen posits that colonisation has left a deep imprint on the consciousness of people all around the world. To rip it out would leave far too big a gap for many of us to bridge. Furthermore, we need to preserve the good that the West has brought us (pp. 222-223). Instead, the task is to ‘multiply frames of reference in our subjectivity and worldview’ (p. 223, emphasis mine) beyond western ones which is what he calls ‘inter-referencing’.

Apart from decentring the West, inter-referencing propels us to look beyond our immediate shores to the ‘imaginary horizon’ of other Asias and the rest of the non-western world as a way to prevent ourselves from getting too self-absorbed. In other words, we look to the region, be it the immediate region of East Asia, like Japan and Korea, or the extended region of Asia, such as South and Southeast Asia, or even better, the broader landscape of the non-western world, like the Pacific Islands, Africa, Latin America, and so on. One key implication for reading the Bible is that the distilling of these perspectives from the wider region is meant to help us transcend our own narcissistic tendencies.

Much more can be said about how this book might help us think differently about ‘doing theologies in Asian ways with Asian resources’, but space forbids it for I have already extended that grace. Let me conclude with one final thought that this book is not a prescription of what it means to do Asia as method, but rather a provocation, an inspiration, an encouragement, a practice maybe, and more boldly if I may, a vision.

[1] See for instance, a recent lecture by Huang Po Po entitled ‘Doing Theologies in Asian Ways with Asian Resources – An Introduction to A Theological Movement Launched by PTCA’. Theology_in_asian_ways.pdf (globethics.net).